- English

- Chinese

- French

- German

- Portuguese

- Spanish

- Russian

- Japanese

- Korean

- Arabic

- Irish

- Greek

- Turkish

- Italian

- Danish

- Romanian

- Indonesian

- Czech

- Afrikaans

- Swedish

- Polish

- Catalan

- Esperanto

- Hindi

- Lao

- Albanian

- Amharic

- Armenian

- Azerbaijani

- Belarusian

- Bengali

- Bosnian

- Bulgarian

- Cebuano

- Chichewa

- Corsican

- Croatian

- Dutch

- Estonian

- Filipino

- Finnish

- Frisian

- Galician

- Georgian

- Gujarati

- Haitian

- Hausa

- Hawaiian

- Hebrew

- Hmong

- Hungarian

- Icelandic

- Igbo

- Javanese

- Kannada

- Kazakh

- Khmer

- Kurdish

- Kyrgyz

- Latin

- Latvian

- Lithuanian

- Luxembou..

- Macedonian

- Malagasy

- Malay

- Malayalam

- Maltese

- Maori

- Marathi

- Mongolian

- Burmese

- Nepali

- Norwegian

- Pashto

- Persian

- Punjabi

- Serbian

- Sesotho

- Sinhala

- Slovak

- Slovenian

- Somali

- Samoan

- Scots Gaelic

- Shona

- Sindhi

- Sundanese

- Swahili

- Tajik

- Tamil

- Telugu

- Thai

- Ukrainian

- Urdu

- Uzbek

- Vietnamese

- Welsh

- Xhosa

- Yiddish

- Yoruba

- Zulu

- Kinyarwanda

- Tatar

- Oriya

- Turkmen

- Uyghur

Welding plate foot environmental impact?

2026-01-31

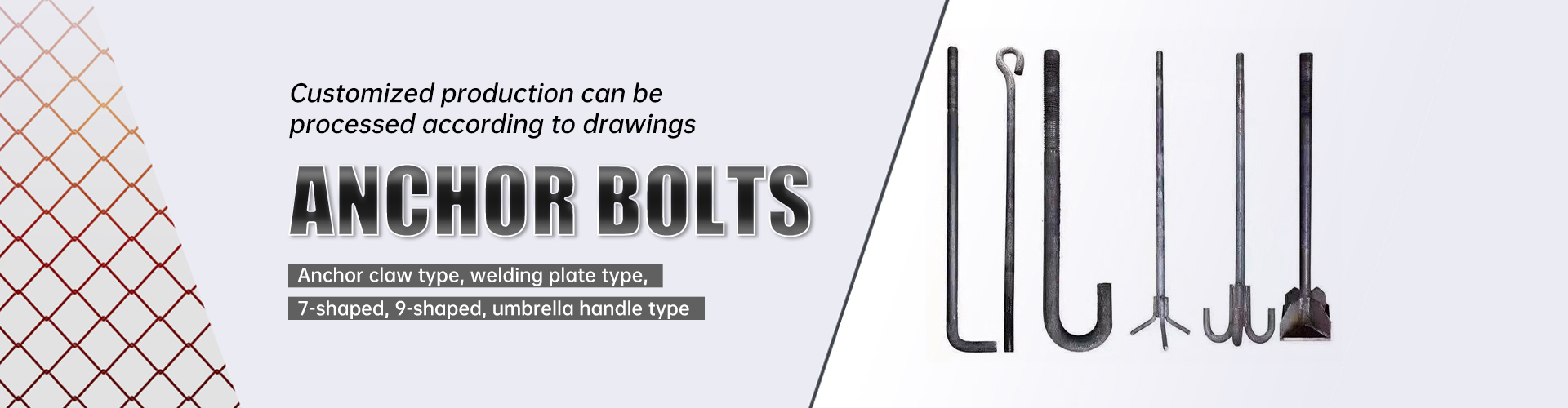

When you hear ‘welding plate foot’, most folks in fabrication think about load capacity, material specs, or maybe corrosion resistance. The environmental side? Often an afterthought, something for the compliance paperwork. But having sourced and installed these components on everything from temporary event stages to permanent industrial platforms, I’ve seen the impact ripple out in ways that aren’t on the spec sheet. It’s not just about the steel you weld; it’s about everything that touches it, from the mill to the jobsite dumpster.

The Hidden Lifecycle of a Plate Foot

Let’s start at the beginning. That chunk of steel, often a simple welded base plate or a more complex adjustable foot, doesn’t just appear. For a standard carbon steel foot, the environmental bill starts with mining and iron ore processing. The energy intensity is staggering. But here’s a practical point we often miss: the Soldadura plaka oina design itself dictates material waste. A poorly designed foot with excessive material ‘just to be safe’ doesn’t just cost more; it means more ore mined, more coal burned in the blast furnace, and more CO2 from the mill. I recall a project where we switched from a bulky, custom-cast foot to a simpler, fabricated plate-and-pipe design from a supplier like Handan Zitai Fastener Manufacturing Co., Ltd.. The weight saving per unit was minor, maybe 15%, but across 5000 units, that was tons of raw steel—and embodied carbon—we simply didn’t need to ship across the globe.

Then there’s the coating. Hot-dip galvanizing is the gold standard for corrosion protection, and for good reason. But that zinc layer comes from its own energy-intensive process and creates wastewater treatment challenges. On a job in a coastal area, we once used pre-galvanized plate for feet, thinking we were being smart. Bad move. The welding burned off the zinc around the seams, creating fumes that required extra ventilation (more energy for fans) and then we had to touch up with cold galvanizing spray—another can of chemicals. The total environmental footprint of that ‘fix’ probably outweighed just using untreated plate and painting it properly later. A lesson in half-measures.

Transport is another sneaky one. Sourcing from a major production hub like Yongnian District in Handan, which bills itself as China’s largest standard part base, makes logistical sense. The convenience of being near major rail and road links, as with Zitai’s location, cuts down on freight fuel. But it creates a centralized model. If you’re building in North America and your feet are coming from Hebei, the maritime shipping emissions are a huge chunk of the product’s lifecycle impact. Sometimes, a locally fabricated foot from a smaller shop, even at a higher unit cost, can have a lower total carbon cost. It’s a calculation we’re only starting to make formally.

On-Site Realities and Fume Management

This is where theory meets the grinder, literally. The environmental impact during installation is immediate and local. Welding fumes are the obvious villain—a mix of metal oxides, shielding gas by-products, and sometimes hexavalent chromium if you’re working with stainless. We’ve all seen the hazy cloud around a welder. The health impact on workers is primary, but that particulate matter doesn’t just vanish; it settles on the site and washes into soil or drainage eventually. Using low-fume welding wires helps, but they’re more expensive, and on tight-budget jobs, they’re the first thing to get value-engineered out.

Power source efficiency matters more than you’d think. An old, diesel-driven welding rig guzzling fuel while you tack on plate feet is a classic site inefficiency. On a remote site without grid power, it’s unavoidable. But I’ve pushed for electric rigs where possible, and even looked at portable battery units for small tack welds. The adoption is slow. The bigger issue is arc-on time. A well-designed Soldadura plaka oina with clear fit-up and jigging gets welded fast. A poorly designed one requires adjustment, re-cutting, and more welding. That extra arc time is more electricity, more filler metal, more fumes. Design for manufacturability isn’t just an engineering term; it’s an environmental one.

Then there’s the ancillary stuff. Cutting the plate to size generates scrap. Are you using oxy-fuel, which burns more gas and creates iron oxide scale, or plasma, which is cleaner but needs clean, dry air? The pre-cleaning solvents for the steel, the anti-spatter sprays—all small consumables that add up to hazardous waste streams on a large project. We started collecting empty aerosol cans separately after a site manager got hit with a surprisingly large waste disposal fee. It was a nuisance, but it forced us to look at bulk application methods instead.

Longevity vs. Replacement: The Durability Equation

The most significant environmental lever is often product life. A plate foot that corrodes and fails in five years, causing a structure to be propped up and replaced, is a disaster compared to one that lasts thirty. This is where material choice and protection are paramount. It’s tempting to use plain carbon steel and a cheap paint job for indoor, dry applications. But what if the building use changes? I’ve seen warehouse storage feet turned into support for a small processing line with occasional moisture. The feet rusted at the weld seam, a failure point that’s hard to inspect. The retrofit—jack up the structure, cut out the old, weld in the new—was incredibly disruptive and resource-heavy.

This is where reputable manufacturers who understand material science add value. A company operating in a major industrial base like Handan’s Yongnian District isn’t just a warehouse; they see the failure modes from clients across industries. They can advise on material grades—like moving from Q235 to weather-resistant steel for a marginal cost increase—or on better galvanizing standards. Their ordeinu might not scream about sustainability, but their product data sheets on coating thickness and material certs tell the real story. A thicker zinc coating or a duplex coating system might increase initial impact, but it prevents a multiply larger impact from premature replacement.

The adjustability factor is another durability play. An adjustable plate foot with a threaded rod or a sliding mechanism allows for leveling on uneven foundations. This can prevent stress concentrations and fatigue. But every moving part is a potential failure point. I’ve seen cheap adjustable feet where the locking mechanism seizes or the threads rust solid, making them non-adjustable and effectively a flawed fixed foot. The environmental cost here is in the complexity of the part (more machining) without realizing the longevity benefit. Sometimes, a simple, robust, fixed foot on a properly prepared base is the greener choice.

End-of-Life: Scrap Isn’t the End

We rarely design for demolition, but we should. At end-of-life, a structure is torn down. What happens to the welded plate feet? If they’re welded directly to a primary beam, they’re often torched off. That’s more energy and fumes. If they’re bolted—which some designs allow for—they can be unbolted, cleaned, and potentially reused or recycled more efficiently. Steel is highly recyclable, but the coating complicates things. Galvanized steel can be recycled, but the zinc volatilizes in the furnace and is often lost, or it contaminate the furnace linings. It’s still better than landfill, but it’s a loss loop.

On a decommissioning project for an old factory, we tried to salvage some plate feet. The ones that were simply dirty were fine. The ones with thick, lead-based paint (from an older era) became a hazardous waste problem. The disposal cost for those few feet was higher than the scrap value of the clean steel. Now, we note the coating systems used in our as-built docs, not just for maintenance, but for future demolition. It feels like writing a note for someone 50 years from now, but that’s the kind of lifecycle thinking we need.

So, is there a green welding plate foot? Not really. There’s a spectrum of less-bad options. It’s a trade-off between initial embodied impact (material, coating, transport) and long-term performance (durability, adaptability). The lowest-impact foot is the one you don’t have to use—where the design eliminates the need. The next best is an appropriately specified, durable, efficiently produced foot that minimizes on-site waste and lasts the life of the structure. It’s not a sexy topic, but every welded connection, even a humble base plate, carries this hidden weight. Ignoring it doesn’t make it lighter.

Practical Shifts and Unanswered Questions

So what changes on the ground? First, specification. Instead of just calling for welded base plate, ASTM A36, galvanized, we’re starting to add notes about material sourcing (prefer recycled content steel), coating type (specify minimum thickness, avoid cadmium), and even prefer suppliers with environmental management systems. It forces a conversation. When you email a supplier like Handan Zitai Fastener with these questions, you quickly learn who’s on top of their supply chain and who isn’t.

Second, on-site practice. We’re bundling welding of all plate feet to maximize arc-on time for fume extraction systems. We’re segregating metal scrap cleanly. Small things. The big hurdle is cost accounting. The environmental cost is externalized—it’s not on our P&L, it’s on the planet’s. Until carbon pricing or stricter regulations hit fabrication hard, the financial incentive for the greener option is often weak or based on corporate ESG goals, which can be the first thing cut in a downturn.

Finally, there’s innovation, but it’s slow. Are there bio-based, non-toxic anti-spatter alternatives that work as well? Can we design more with bolt-on feet for easier deconstruction? I’ve seen prototypes of feet made from higher-strength, thinner steel, or even composite materials for specific applications, but adoption in the conservative construction world is glacial. The welding plate foot is a commodity. Its environmental impact is woven into the fabric of heavy industry. Untangling it means looking at every single step, from the mill in Hebei to the scrap yard in Rotterdam, and asking if there’s a slightly better way. Most of the time, there is. It’s just rarely the cheapest or easiest path.