- Chinese

- French

- German

- Portuguese

- Spanish

- Russian

- Japanese

- Korean

- Arabic

- Irish

- Greek

- Turkish

- Italian

- Danish

- Romanian

- Indonesian

- Czech

- Afrikaans

- Swedish

- Polish

- Basque

- Catalan

- Esperanto

- Hindi

- Lao

- Albanian

- Amharic

- Armenian

- Azerbaijani

- Belarusian

- Bengali

- Bosnian

- Bulgarian

- Cebuano

- Chichewa

- Corsican

- Croatian

- Dutch

- Estonian

- Filipino

- Finnish

- Frisian

- Galician

- Georgian

- Gujarati

- Haitian

- Hausa

- Hawaiian

- Hebrew

- Hmong

- Hungarian

- Icelandic

- Igbo

- Javanese

- Kannada

- Kazakh

- Khmer

- Kurdish

- Kyrgyz

- Latin

- Latvian

- Lithuanian

- Luxembou..

- Macedonian

- Malagasy

- Malay

- Malayalam

- Maltese

- Maori

- Marathi

- Mongolian

- Burmese

- Nepali

- Norwegian

- Pashto

- Persian

- Punjabi

- Serbian

- Sesotho

- Sinhala

- Slovak

- Slovenian

- Somali

- Samoan

- Scots Gaelic

- Shona

- Sindhi

- Sundanese

- Swahili

- Tajik

- Tamil

- Telugu

- Thai

- Ukrainian

- Urdu

- Uzbek

- Vietnamese

- Welsh

- Xhosa

- Yiddish

- Yoruba

- Zulu

- Kinyarwanda

- Tatar

- Oriya

- Turkmen

- Uyghur

How does AI boost sustainability in manufacturing?

2026-01-09

When people hear AI in manufacturing, they often jump to visions of fully autonomous, lights-out factories. That’s a flashy goal, but it’s not where the real, gritty work of boosting sustainability is happening today. The true impact is more nuanced, often hidden in the daily grind of optimizing energy consumption, slashing material waste, and making supply chains less chaotic. It’s less about robots taking over and more about intelligent systems providing the granular visibility we’ve always lacked to make decisions that are both economically and environmentally sound. The link between AI and sustainability isn’t automatic; it requires a deliberate shift in what we choose to measure and control.

Beyond the Hype: Energy as the First Frontier

Let’s start with energy, the most direct cost and carbon footprint item. For years, we relied on scheduled maintenance and broad-strokes efficiency ratings. The game-changer is embedding sensors and using AI for predictive energy optimization. I’m not talking about just turning machines off. It’s about understanding the dynamic load of an entire production line. For instance, an AI model can learn that a specific stamping press draws a surge of power not just during operation, but for 15 minutes after, as cooling systems run. By analyzing production schedules, it can suggest micro-delays between batches to avoid simultaneous peak draws from multiple presses, flattening the energy curve without impacting throughput. This isn’t theoretical; I’ve seen it shave 8-12% off the energy bill in a forging facility, which is massive at scale.

The tricky part is data quality. You need granular, time-series data from the machine, the substation, and even the grid if possible. One failed project early on was trying to optimize a heat treatment furnace without accurate gas flow meters. The AI model was essentially guessing, and the optimizations risked compromising the metallurgical properties of the parts. We learned the hard way: you can’t manage what you can’t measure accurately. The AI is only as good as the sensory inputs it gets.

This leads to a subtle point: AI often justifies deeper instrumentation. To make a sustainability case for AI, you first invest in better metering. It’s a virtuous cycle. Once you have that data stream, you can move from prediction to prescriptive action—like automatically adjusting compressor pressure setpoints based on real-time demand in a pneumatic network, something that was always set for the worst-case scenario, wasting huge amounts of energy.

The War on Waste: From Scrap Heaps to Digital Twins

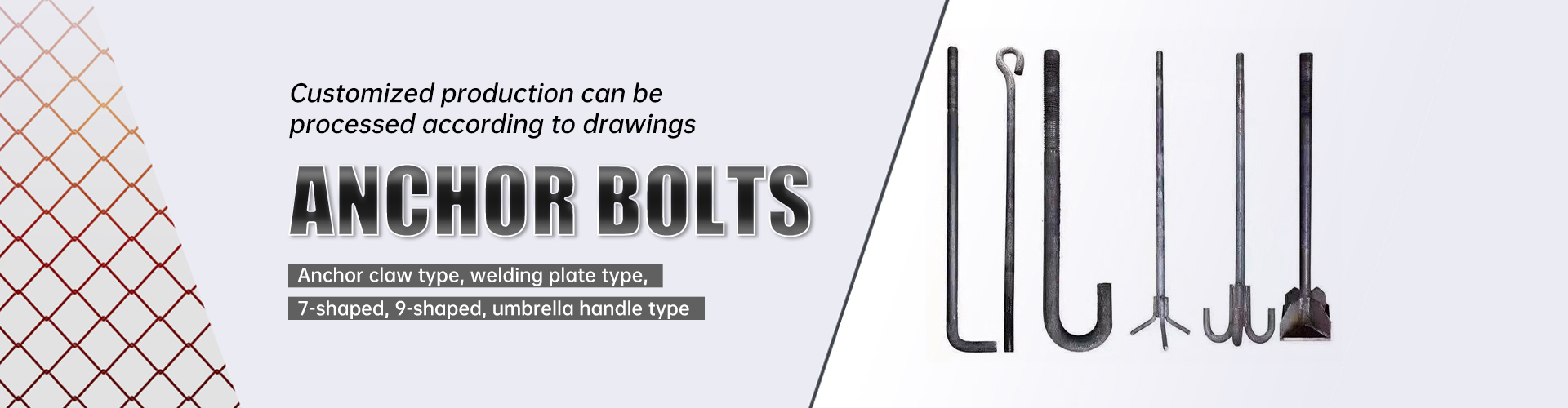

Material waste is pure financial and environmental loss. In fastener manufacturing, like at a company such as Handan Zitai Fastener Manufacturing Co., Ltd. located in China’s major standard part production base, the traditional approach involves post-production inspection: a batch is made, some are sampled, and if defects are found, the whole lot might be scrapped or reworked. That’s incredibly wasteful.

Computer vision for real-time defect detection is now table stakes. But the more profound use of AI is in process parameter optimization to prevent waste from being created in the first place. By feeding data from the cold heading process—wire diameter, temperature, machine speed, die wear—into a model, we can predict the likelihood of head cracks or dimensional inaccuracies before a single piece is made. The system can then recommend adjustments, say, a slight increase in annealing temperature or a reduction in feed rate.

I recall a project where we built a digital shadow (a simpler version of a full digital twin) for a bolt production line. The goal was to minimize the trim loss – the leftover wire after a bolt is cut. By analyzing order portfolios and machine constraints, the AI scheduling system could sequence orders to use wire coils more completely, reducing trim waste from an average of 3.2% to under 1.7%. It sounds small, but across thousands of tons of steel annually, the savings in raw material and the associated carbon emissions from steel production are substantial. You can see how companies in hubs like Yongnian District, with their high volume output, stand to gain immensely from such granular optimizations.

Supply Chain Resilience and the Carbon Footprint

This is where it gets complex. A sustainable supply chain isn’t just about choosing a green supplier; it’s about efficiency and resilience to avoid emergency, carbon-intensive air freight. AI-driven demand forecasting, when it works, smooths out production, reducing the need for overtime (which often means less efficient, energy-intensive runs) and panic ordering.

We integrated multi-tier supply chain risk analysis with logistics optimization for a client. The system monitored weather, port congestion, and even supplier region energy mix (e.g., is their grid running on coal or renewables today?). It suggested rerouting shipments to slower but lower-emission sea freight when timelines allowed, or consolidating loads to fill containers to 98% capacity instead of the typical 85%. The sustainability gain here is indirect but powerful: it embeds carbon efficiency into daily logistical decisions.

The failure mode here is over-optimization. One model suggested always using a single, very green but capacity-constrained supplier to minimize transport emissions. It failed to account for the risk of a shutdown, which eventually happened, forcing a scramble to multiple, less optimal suppliers. The lesson was that sustainability objectives must be balanced with robustness constraints in the AI’s objective function. You can’t just minimize carbon; you have to manage risk.

The Human Element: Augmented Decision-Making

This is critical. AI doesn’t run the factory; people do. The most effective implementations I’ve seen are where AI acts as an advisor. It flags an anomaly: The energy consumption per unit on Line 3 is 18% above benchmark for the current product mix. Probable cause: Bearing wear in Conveyor Motor B-12, estimated efficiency loss 22%. It gives the maintenance team a targeted, prioritized task with a clear sustainability and cost impact.

This changes the culture. Sustainability stops being a separate KPI from production efficiency. When the floor manager sees that optimizing for lower scrap rates also reduces energy and raw material use per good part, the goals align. Training the AI also trains the people. To label data for a defect detection model, quality engineers have to deeply analyze failure modes. This process itself often leads to process improvements before the model is even deployed.

Resistance is natural. There’s a valid fear of black box recommendations. That’s why explainability is key. If the system says reduce furnace temperature by 15°C, it must also provide the reasoning: Historical data shows runs with parameters X and Y at this lower temp resulted in identical hardness with 8% less natural gas consumption. This builds trust and turns the AI into a collaborative tool for sustainable manufacturing.

Looking Ahead: The Integration Challenge

The future isn’t in standalone AI applications for energy or quality. It’s in integrated process optimization that balances multiple, sometimes competing, objectives: throughput, yield, energy use, tool wear, and carbon footprint. This is a multi-objective optimization problem that is beyond human calculation in real-time.

We’re piloting systems that take a customer order and dynamically determine the most sustainable production route. Should this batch of fasteners be made on the older, slower line that’s now powered by the factory’s new solar array, or on the newer, faster line that’s grid-powered but has a lower scrap rate? The AI can calculate the net carbon impact, including embodied carbon in any potential scrap, and recommend the truly optimal path. This is next-level thinking.

The final hurdle is lifecycle assessment integration. The real boost to sustainability will come when the AI in manufacturing has access to data on the full lifecycle impact of materials and processes. Choosing between a zinc plating and a new polymer coating isn’t just a cost decision; it’s a decision about chemical use, durability, and end-of-life recyclability. We’re not there yet, but the foundational work—getting processes digitized, instrumented, and under adaptive control—is what makes that future possible. It’s a long, unglamorous road of solving one small, wasteful problem at a time.