- English

- Chinese

- French

- German

- Portuguese

- Spanish

- Russian

- Japanese

- Korean

- Arabic

- Irish

- Greek

- Turkish

- Italian

- Danish

- Romanian

- Indonesian

- Czech

- Afrikaans

- Swedish

- Polish

- Catalan

- Esperanto

- Hindi

- Lao

- Albanian

- Amharic

- Armenian

- Azerbaijani

- Belarusian

- Bengali

- Bosnian

- Bulgarian

- Cebuano

- Chichewa

- Corsican

- Croatian

- Dutch

- Estonian

- Filipino

- Finnish

- Frisian

- Galician

- Georgian

- Gujarati

- Haitian

- Hausa

- Hawaiian

- Hebrew

- Hmong

- Hungarian

- Icelandic

- Igbo

- Javanese

- Kannada

- Kazakh

- Khmer

- Kurdish

- Kyrgyz

- Latin

- Latvian

- Lithuanian

- Luxembou..

- Macedonian

- Malagasy

- Malay

- Malayalam

- Maltese

- Maori

- Marathi

- Mongolian

- Burmese

- Nepali

- Norwegian

- Pashto

- Persian

- Punjabi

- Serbian

- Sesotho

- Sinhala

- Slovak

- Slovenian

- Somali

- Samoan

- Scots Gaelic

- Shona

- Sindhi

- Sundanese

- Swahili

- Tajik

- Tamil

- Telugu

- Thai

- Ukrainian

- Urdu

- Uzbek

- Vietnamese

- Welsh

- Xhosa

- Yiddish

- Yoruba

- Zulu

- Kinyarwanda

- Tatar

- Oriya

- Turkmen

- Uyghur

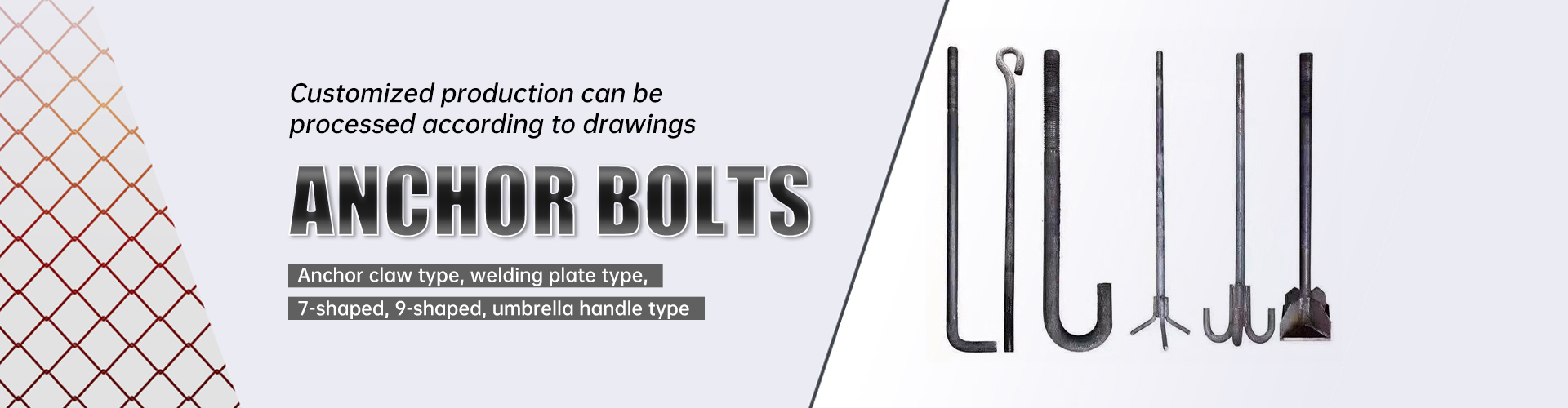

Umbrella handle foot tech innovations?

2026-01-31

When most people hear umbrella handle foot tech, they probably think of that little rubber tip at the bottom. If they think of it at all. That’s the common misconception—it’s just a piece of rubber, right? How much innovation could there possibly be? Having been in the fastener and component sourcing game for years, specifically around hardware for consumer goods like umbrellas, I can tell you that’s where the real, gritty engineering often gets overlooked. The foot, that terminal piece where the handle meets the ground or hooks onto a table edge, is a nexus of material science, ergonomics, and manufacturing precision. It’s a small part that solves big, annoying problems: slippage, wear, attachment failure, and user discomfort. The so-called innovations aren’t about reinventing the wheel; they’re about refining a point of contact that most users take for granted until it fails.

The Baseline: It’s Never Just a Cap

Let’s start with the standard issue. For decades, the default was a simple PVC or TPR (thermoplastic rubber) cap, press-fitted or lightly glued onto the metal tube end. The goal was basic: prevent the metal from scratching floors and provide minimal grip. The failure modes were predictable. The adhesive would degrade, the cap would fall off and get lost—a minor catastrophe rendering the umbrella annoying to stand upright. Or the rubber would harden and crack after a season in the sun and rain, thanks to UV degradation and ozone exposure. This wasn’t a design flaw per se; it was a cost-driven material choice. The innovation started not with wanting to make something smart, but with wanting to solve this specific, persistent failure point that drove customer complaints and returns.

We saw a shift towards overmolding. Instead of a separate cap, the soft-touch material is injection-molded directly onto the handle’s end. This creates a mechanical bond far superior to adhesive. It’s a process borrowed from tool handles. The key here is material compatibility—getting the plastic or metal substrate and the overmold elastomer to bond chemically during cooling. Not all combinations work. An early trial with a certain polypropylene handle and a specific TPE blend resulted in a clean separation after thermal cycling tests. It looked perfect out of the mold but failed in real-world temperature swings. That’s the hidden detail: true innovation in this space is often invisible, buried in supplier material datasheets and bonding tests.

This leads to the role of specialized manufacturers. You can’t just ask any injection molder to do this well. It requires expertise in multi-material molding and a deep understanding of polymer behavior. This is where a connection to a precision manufacturing hub becomes critical. For instance, working with component suppliers from regions like Yongnian in Hebei, China, which is a massive base for standard parts and fasteners, provides access to this concentrated expertise. A company like Handan Zitai Fastener Manufacturing Co., Ltd., operating from that major production base, understands the tolerances and material specs needed not just for a screw, but for a component like an overmolded foot. Their experience in volume production of precision parts translates into consistency for something as seemingly simple as an umbrella foot. You can find their approach to material and manufacturing logistics detailed on their platform at https://www.zitaifasteners.com.

Material Evolution: Beyond Simple Rubber

The quest for better grip and durability pushed materials beyond basic rubber. Thermoplastic Elastomers (TPEs) and Thermoplastic Polyurethanes (TPUs) became game-changers. They offer a wider range of durometer (hardness), better UV resistance, and improved fatigue life. A softer, gel-like TPE foot on a walking stick umbrella provides incredible cushioning and anti-slip properties, a genuine comfort innovation for users who rely on it for stability. However, softer isn’t always better. A gel foot on a heavy golf umbrella can deform permanently under load, looking sloppy and losing its shape. It’s a trade-off.

Then there’s the incorporation of additives. Silica additives for abrasion resistance, carbon black for UV stabilization (though it limits color options), and even antimicrobial agents for a premium health-conscious pitch. I recall a project for a travel umbrella brand that wanted an antimicrobial foot. Sounded great on the marketing sheet. The reality was the additive, usually silver ions or triclosan at the time, could migrate to the surface and get worn off quickly, or worse, affect the polymer’s flexibility. The added cost was significant, and the real-world benefit for a part that touches the ground and your hand intermittently was… debatable. It was an innovation that looked better in a catalog than in daily use.

The latest frontier I’m seeing is in sustainable materials. Bio-based TPEs derived from plant oils, or compounds with recycled rubber content. The challenge is performance parity. A foot made from a new bio-TPE might have excellent green credentials but fail a critical compression set test—meaning it doesn’t spring back after being squashed in a bag all day. The innovation is slow, iterative, and full of these small, frustrating compromises that never make it to the product description.

Ergonomics and Secondary Functions

This is where it gets interesting. The foot isn’t just an end cap; it’s a functional interface. For hook handles, the foot’s shape determines how securely it hangs. A flat, wide foot with a high-friction material is good for thick table edges. A narrower, curved profile might be better for delicate chair backs. Some designs now incorporate a slight recess or a magnetic element in the foot. The recess aligns with a protrusion on the handle’s side, creating a positive click feel when the umbrella is rolled closed—a small but satisfying user feedback detail.

I worked on a prototype where the foot housed a weak rare-earth magnet. The idea was the umbrella could stick to a metallic frame of a patio chair or a car door frame for hands-free drying. It was clever, but the magnet added cost and weight, and its strength was a constant headache. Too weak, and it was useless; too strong, and it would snap violently to metal surfaces, potentially damaging the fabric. We also had to shield it to prevent it from erasing hotel key cards in a bag. A classic case of a tech innovation creating more problems than it solved. It never went to mass production.

A more successful, low-tech innovation is the integrated wear indicator. Using a two-shot molding process, the outer layer of the foot is a dark color, while the core is a bright, contrasting color. As the foot wears down from abrasion, the bright core becomes visible, signaling to the user that replacement might be needed soon. It’s simple, effective, and adds perceived value without complex electronics. This kind of thinking represents the best of handle foot tech: solving a real problem with elegant, manufacturable simplicity.

Attachment and Structural Integration

How the foot stays on is arguably more important than what it’s made of. The press-fit cap is the old enemy. The innovation is in making the foot a structural part of the handle assembly. One method is the trapped foot design. The foot is molded with a flange or collar. During handle assembly, the lower part of the handle’s shaft or a separate ferrule is crimped or screwed over this flange, physically trapping it. It cannot fall off unless the entire handle disassembles. This is a robust solution common in higher-end umbrellas.

Another approach is threading. The handle end has a male thread, and the foot has a corresponding female thread, sometimes with a locking adhesive patch. This allows for replacement, which is a nice theoretical benefit. In practice, users almost never replace a worn foot; they just live with it or buy a new umbrella. The cost of adding threads to both parts often outweighs the benefit. However, for modular or build-your-own premium umbrella brands, this threaded foot system allows for customization—different colors or materials—which is a marketing innovation more than a practical one.

The most integrated design eliminates the separate foot altogether. The handle material itself, often a durable nylon or ABS plastic, is engineered to have a textured, high-friction, and slightly resilient end. This is achieved through the handle’s mold design and material choice. It’s the ultimate simplification, reducing parts count and assembly steps. The downside? If that textured area wears smooth, you can’t fix it. The entire handle is compromised. It pushes the durability requirement back onto the primary handle material, which can drive up its cost and specification. It’s a system-level design choice, not just a component one.

The Manufacturing Reality and Cost Equation

Every innovation discussed hits the wall of cost. A dual-material overmolded foot with a wear indicator requires a more complex mold, two material feeds, and longer cycle times. It might add $0.15 to the unit cost. For a $5 umbrella sold in volume, that’s a massive percentage increase. For a $50 premium umbrella, it’s a no-brainer. The innovation is often just making a better feature cost-viable at a specific price point.

This is where the ecosystem in a place like Yongnian District shows its strength. The density of suppliers for molds, polymers, and finishing services creates efficiency. A manufacturer like Handan Zitai Fastener isn’t just selling a fastener; they’re providing access to an integrated supply chain that can handle the precision required for a multi-shot molded foot. Their location near major transport routes, as noted, is key for logistics, ensuring that these small but critical components move efficiently into global supply chains. The innovation sometimes isn’t in the product design, but in the manufacturing and supply chain agility that makes a new design possible to produce reliably at scale.

Finally, testing is where theory meets reality. A new foot design undergoes shear tests (how much sideways force before it detaches), compression set tests, UV aging tests, and cold impact tests (does the material shatter at -20°C?). I’ve seen beautifully designed feet pass all lab tests only to fail in field trials because of an unanticipated use case—like people using the umbrella as a makeshift walking stick on gravel, subjecting the foot to extreme point-load abrasion no test simulated. Real-world feedback loops are the final, and most humbling, stage of any tech innovation, no matter how small the component.

So, umbrella handle foot tech? It’s a microcosm of industrial design. It’s about the relentless pursuit of solving mundane but universal problems: things slipping, breaking, or getting lost. The innovations are quiet, material-deep, and often hidden in plain sight. They’re less about flashy tech and more about the hard-won knowledge of what works, what lasts, and what truly matters to the hand holding the umbrella at the end of a rainy day.