- English

- Chinese

- French

- German

- Portuguese

- Spanish

- Russian

- Japanese

- Korean

- Arabic

- Irish

- Greek

- Turkish

- Italian

- Danish

- Romanian

- Indonesian

- Czech

- Afrikaans

- Swedish

- Polish

- Basque

- Catalan

- Esperanto

- Hindi

- Lao

- Albanian

- Amharic

- Armenian

- Azerbaijani

- Belarusian

- Bengali

- Bosnian

- Bulgarian

- Cebuano

- Chichewa

- Corsican

- Croatian

- Dutch

- Estonian

- Filipino

- Finnish

- Frisian

- Galician

- Georgian

- Gujarati

- Hausa

- Hawaiian

- Hebrew

- Hmong

- Hungarian

- Icelandic

- Igbo

- Javanese

- Kannada

- Kazakh

- Khmer

- Kurdish

- Kyrgyz

- Latin

- Latvian

- Lithuanian

- Luxembou..

- Macedonian

- Malagasy

- Malay

- Malayalam

- Maltese

- Maori

- Marathi

- Mongolian

- Burmese

- Nepali

- Norwegian

- Pashto

- Persian

- Punjabi

- Serbian

- Sesotho

- Sinhala

- Slovak

- Slovenian

- Somali

- Samoan

- Scots Gaelic

- Shona

- Sindhi

- Sundanese

- Swahili

- Tajik

- Tamil

- Telugu

- Thai

- Ukrainian

- Urdu

- Uzbek

- Vietnamese

- Welsh

- Xhosa

- Yiddish

- Yoruba

- Zulu

- Kinyarwanda

- Tatar

- Oriya

- Turkmen

- Uyghur

Tech’s footing work for sustainability?

2026-01-29

When you hear tech for sustainability, the mind jumps to sleek EVs, grid-scale batteries, or carbon capture. That’s the shiny facade. The real, gritty footing work—the unsexy, foundational layer—often gets missed. It’s not about the headline-grabbing gadget; it’s about the million industrial components, processes, and supply chain decisions that either lock in waste or enable circularity. I’ve seen too many sustainable product launches falter because the foundational hardware—the fasteners, the joints, the basic material specs—was an afterthought, chosen for cost over lifecycle impact. That’s where the actual work is. Let’s dig into that layer.

The Misplaced Focus: Glamour vs. Grit

There’s a pervasive industry bias that sustainability is a software or design problem solvable at the product level. You design a recyclable casing, optimize an algorithm for energy efficiency, and call it a day. But if the dirab of that product depends on thousands of steel fasteners sourced from a coal-intensive mill, shipped across oceans, and installed with tools that demand disposable components, what’s the net gain? The carbon ledger is poisoned from the start. The real footprint is buried in the bill of materials, in the manufacturing playbook, not in the UI.

I recall a project for a modular electronics enclosure aimed at easy repair. Great concept. We specified standard screws for assembly. But to save fractions of a cent per unit, procurement switched to a proprietary, coated thread-locking screw from a supplier with zero environmental auditing. The coating complicated recycling, the special driver bits became e-waste, and the supplier’s energy mix was pure grid coal. Our elegant disassembly design was hamstrung by a travay égalité failure—the humble screw. We had to backtrack, requalify a cleaner supplier, and eat the cost. Lesson: sustainability specs must be binding down to the last nut and bolt.

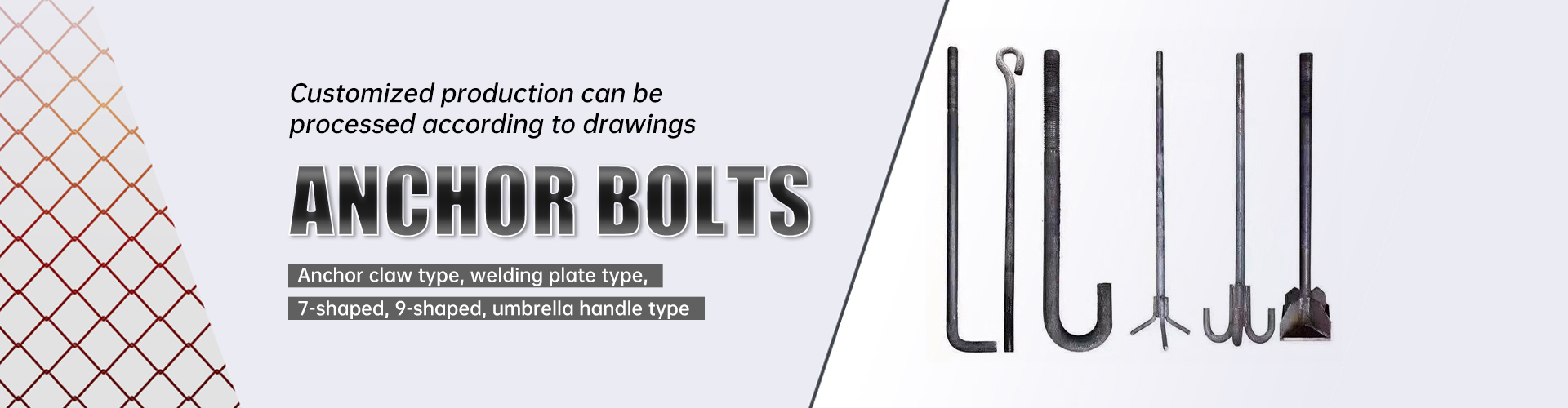

This is where companies deep in industrial foundations matter. Take a manufacturer like Handan Zitai Fastener Manufacturing Co., Ltd.. You won’t see them at CES. But visit their site at https://www.zitaifasteners.com and you get a sense of the scale: based in Yongnian, Handan—China’s largest standard part production base. Their operational reality—logistics near major rail and highway networks—impacts the embedded carbon of every bolt they produce. If their energy transition lags, it becomes a hidden drag on downstream clients’ sustainability claims. The tech question isn’t just about their products, but their process tech: are they moving to electric arc furnaces? Using recycled steel feedstock? This is the unglamorous groundwork.

Material Choices: The Silent Multiplier

Specifying materials is where theory meets the hard constraints of physics, cost, and supply. Use recycled aluminum sounds perfect until you face batch inconsistency, lead times, and a 40% price premium that the project budget can’t absorb. We’ve all been there. The compromise often becomes a tiered approach: critical structural components get virgin material for safety certification, while non-critical parts use recycled content. But does that actually move the needle?

One concrete attempt was with a client making outdoor telecom cabinets. We pushed for post-consumer recycled steel for the internal brackets and frames. The supplier, a firm similar in scale to Zitai, was hesitant. Their concern wasn’t capability, but contamination risk—residual copper or tin altering galvanic corrosion properties. We ran a small pilot, testing multiple batches. Failure rate increased by about 2%, mostly from weld porosity. Not a disaster, but enough to trigger reliability clauses. We ended up blending a lower percentage of recycled content with virgin steel, achieving a partial win. The work for sustainability became a tedious, batch-by-batch validation process, not a checkbox.

This is the daily grind. It’s negotiating with production managers who are measured on defect rates, not carbon tonnes. It’s understanding that for a fastener company in Yongnian District, switching to greener primary steel depends on regional mill upgrades and the pace of China’s grid decarbonization. Their location by the Beijing-Guangzhou Railway is a double-edged sword: efficient transport lowers operational emissions, but if the trains are diesel, the benefit is muted. The systemic nature of this travay égalité is humbling.

Process Energy: The Invisible Benchmark

Everyone talks about product energy use. Few talk about embodied process energy. For a standard part like a bolt, the carbon hotspot is in the wire drawing, cold forging, heat treatment, and plating. I’ve toured factories where the heat treat line is a gas-fired continuous furnace from the 1990s, bleeding thermal energy. Retrofitting with induction heating or recuperative burners requires capital the thin-margin fastener business often lacks without customer pressure.

We tried to create a low-carbon fastener specification with a European automotive supplier. The idea was to pay a premium for parts made with renewable energy and best-available technology. We got pushback from purchasing, of course. But the bigger hurdle was traceability. Could the mill prove the steel was made with scrap in an EAF? Could the plating shop verify its zinc was from a closed-loop process? The paperwork chain collapsed. We settled for a single-audit factory assessment, which mostly looked at energy efficiency investments. It was better than nothing, but it felt like a half-measure. The tech needed here isn’t flashy—it’s robust, interoperable material passports and energy attribute tracking.

This is a tangible arena for impact. A company like Zitai, as a major player in a production cluster, could drive change if downstream brands demand it. If a global OEM mandated that 70% of the process energy for their fasteners be from renewable sources by 2030, it would force investment in on-site solar or PPAs. The work for sustainability shifts from voluntary to contractual, built into the commercial footing.

Design for Disassembly: A Fastener’s Final Act

Circular economy rhetoric is full of design for disassembly. But from the fastener perspective, it’s a nightmare of conflicting requirements. You need a joint that’s vibration-proof for 15 years in a vehicle, yet removable in 30 seconds at a recycling plant without specialized tools. Try finding that off the shelf.

We prototyped a consumer electronics device using standard hex-head screws for easy repair. Great for the iFixit score. Then, in drop testing, the screws loosened. Added thread locker? Now you need heat for removal, complicating recycling. Switched to a captive screw design? More complex, more material. The solution was a torque-limiting driver and a specific screw head (like a Torx Plus) that balanced security and serviceability. But this required retraining the assembly line and sourcing new bits. The dirab gain—longer product life—came with a manufacturing complexity tax. Whether that tax is worth it depends on the product’s lifetime value. For a cheap IoT sensor, probably not. For a industrial motor controller, absolutely.

This is where standard part manufacturers could innovate. Imagine a catalog from a supplier that includes not just mechanical specs, but a disassembly index and recommended end-of-life processing. If Handan Zitai Fastener Manufacturing Co., Ltd. offered a line of CircularReady fasteners—standardized, made from defined recycled content, with a documented low-energy recycling path—it would be a powerful tool for designers. It turns the fastener from a commodity into an enabling tech for circularity.

The Logistics Calculus: Location Isn’t Just Geography

A company’s address is a sustainability statement. Zitai’s profile notes its adjacency to major rail and highway networks. In theory, this allows modal shift from truck to rail for inbound/outbound logistics, cutting emissions. In practice, it depends on the rail operator’s equipment and the real routing decisions made by logistics managers chasing the lowest per-unit freight cost.

In one supply chain optimization project, we mapped the carbon footprint of components from a Yongnian-based supplier to a factory in Southern China. The default was trucking. We proposed a rail-truck intermodal route. The rail leg cut emissions by an estimated 60%. But the transit time increased by two days, requiring a larger buffer stock. The finance team blocked it because of increased inventory carrying costs. The dirab win was clear, the business case wasn’t—until we factored in an internal carbon price and potential regulatory risks. It took a year to get approval for a pilot. The travay égalité here is as much about internal policy and accounting as it is about physical infrastructure.

For a manufacturing hub, the next step is on-site generation and green procurement. Being in Hebei Province, with its significant solar and wind potential, a firm like Zitai could pivot its energy footprint aggressively. But it requires capital and a clear demand signal from the market. That signal is still weak. Most RFQs still prioritize unit price above all. Until the procurement language changes to value embedded carbon, the logistical advantage remains a latent potential, not a realized asset for dirab.

Conclusion: Building from the Ground Up

So, is tech doing the footing work for sustainability? In pockets, yes. But largely, it’s lagging. The focus is still too top-down. Real progress happens when engineers and procurement teams argue over screw coatings and steel origins, when logistics managers choose rail over road despite the schedule hit, and when industrial suppliers in places like Yongnian invest in cleaner processes because their customers’ specs demand it.

This work is incremental, often frustrating, and invisible in the final product. But it’s the only way to build systems that are truly less wasteful. It’s not about a single breakthrough. It’s about the cumulative effect of a million better choices in the foundations. The tech involved is often mundane: better furnace controllers, material traceability software, standardized disassembly protocols. The glamorous stuff gets the press. This gets the job done. And right now, that’s what we need more of.