- English

- Chinese

- French

- German

- Portuguese

- Spanish

- Russian

- Japanese

- Korean

- Arabic

- Irish

- Greek

- Turkish

- Italian

- Danish

- Romanian

- Indonesian

- Czech

- Afrikaans

- Swedish

- Polish

- Catalan

- Esperanto

- Hindi

- Lao

- Albanian

- Amharic

- Armenian

- Azerbaijani

- Belarusian

- Bengali

- Bosnian

- Bulgarian

- Cebuano

- Chichewa

- Corsican

- Croatian

- Dutch

- Estonian

- Filipino

- Finnish

- Frisian

- Galician

- Georgian

- Gujarati

- Haitian

- Hausa

- Hawaiian

- Hebrew

- Hmong

- Hungarian

- Icelandic

- Igbo

- Javanese

- Kannada

- Kazakh

- Khmer

- Kurdish

- Kyrgyz

- Latin

- Latvian

- Lithuanian

- Luxembou..

- Macedonian

- Malagasy

- Malay

- Malayalam

- Maltese

- Maori

- Marathi

- Mongolian

- Burmese

- Nepali

- Norwegian

- Pashto

- Persian

- Punjabi

- Serbian

- Sesotho

- Sinhala

- Slovak

- Slovenian

- Somali

- Samoan

- Scots Gaelic

- Shona

- Sindhi

- Sundanese

- Swahili

- Tajik

- Tamil

- Telugu

- Thai

- Ukrainian

- Urdu

- Uzbek

- Vietnamese

- Welsh

- Xhosa

- Yiddish

- Yoruba

- Zulu

- Kinyarwanda

- Tatar

- Oriya

- Turkmen

- Uyghur

Solid footing in green tech’s future?

2026-01-29

Everyone’s talking about the inevitable boom, but from where I stand, the foundation feels less like concrete and more like shifting sand. The assumption that demand alone will build a stable industry is the first mistake I see repeated.

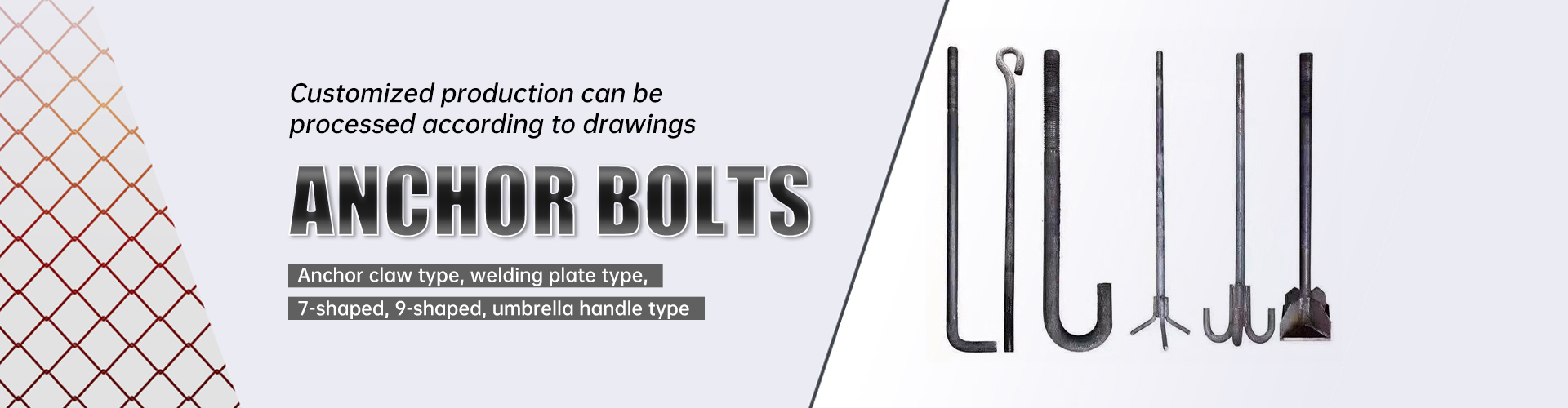

The Hardware Reality Check

You can’t have a green energy transition without the physical stuff holding it together. I’m talking about the unsexy components—the brackets, the clamps, the finkagailu. A solar farm isn’t just panels; it’s a mechanical structure facing decades of wind, rain, and thermal cycling. We learned this the hard way on a project in Nevada. The spec called for standard galvanized steel hardware. Within 18 months, stress corrosion cracking started showing up in the mounting rails. The fix? A complete retrofit with higher-grade, corrosion-resistant alloys, blowing the maintenance budget. It wasn’t a failure of the solar tech; it was a failure of the foundational hardware it relied on.

This is where the supply chain gets real. It’s not just about sourcing the raw lithium or silicon. It’s about having access to specialized, reliable manufacturers for these critical components. I’ve visited factories that claim to serve the renewables sector, only to find their quality control isn’t calibrated for the 25-year lifespans we’re promising investors. The tolerance margins are different. The testing protocols need to be brutal.

For instance, consider a company like Handan Zitai Fastener Manufacturing Co., Ltd. (https://www.zitaifasteners.com). Based in Yongnian, Hebei—China’s largest standard part production base—their logistical advantage being adjacent to major rail and highway networks is precisely the kind of detail that matters at scale. But the real question isn’t location; it’s whether their production lines have adapted to the specific material science demands of, say, a floating solar installation’s constant moisture exposure or the vibrational stresses on a wind turbine’s nacelle. I’ve seen their catalog; the shift from generic industrial bolts to product lines with specific certifications for photovoltaic (PV) mounting systems is a telling sign of the industry’s maturation, or at least its attempt to catch up.

The Integration Gap

There’s a dangerous disconnect between the engineers designing the next-gen battery storage system and the people who have to bolt it to the foundation. I sat in a design review where the electrical specs were flawless, but the mechanical interface drawings were an afterthought—vague notes about adequate anchoring. Adequate according to which standard? The civil engineer’s manual from 1995? This gap creates fragility. It invites field crews to make their own calls, which leads to inconsistency, which leads to points of failure.

We tried to bridge this by creating a simple cross-disciplinary checklist for every project kickoff. It forces the conversation early: What’s the substrate? What’s the thermal expansion coefficient of the assembly? What’s the maintenance access? It sounds basic, but you’d be surprised how often these questions weren’t formally asked. The result was fewer callbacks, plain and simple.

The lesson is that green tech‘s durability is systemic. A weak point in the physical integration can undermine the performance of the most advanced technology. It’s like putting a Formula One engine in a chassis held together with cheap screws. The industry needs more hybrid thinkers—people who understand both the electrochemical potential and the shear strength of a bolted joint.

Cost vs. Lifetime Value Myopia

The procurement pressure is immense, especially with government incentives pushing for rapid deployment. The bidding process often rewards the lowest upfront cost. This creates a perverse incentive to value-engineer the very components that ensure longevity. I’ve fought with project managers over specifying a more expensive stainless steel alloy for coastal sites. The argument is always budget. My counter-argument is the net present value of replacing the entire array in 10 years versus operating it for 30.

This myopia isn’t just financial; it’s reputational. When a high-profile green project fails prematurely due to a mechanical issue, it feeds a narrative that the entire sector is unreliable. We have to start selling the lifetime, not just the launch. This means changing how we write contracts, how we model finances, and how we communicate with stakeholders. The future of the industry depends on trust, and trust is built on things not falling apart.

There are glimmers of change. Some asset owners are now demanding third-party certification for structural components, not just the primary tech. They’re asking for fatigue test data specific to the application. It’s a slower, more expensive path to groundbreaking, but it’s the one that builds a system you can actually bank on for decades.

Material Scarcity on the Ground Level

Much ink is spilled about rare earth elements, but let’s talk about copper, aluminum, and even high-strength steel. The projected rollout of renewables, EV charging infrastructure, and grid upgrades is going to strain global supplies of these conventional materials. We’re already seeing volatile pricing and lead times stretching out. This isn’t a distant threat; it’s affecting project timelines today.

This forces practical adaptations. Can a design use less material without compromising integrity? Is there a viable recycled-content alloy that meets the spec? I was involved in testing a new aluminum composite for cable management systems that used a significant percentage of post-industrial scrap. The performance was comparable, but the supply chain was more resilient. It’s these unglamorous material innovations that will provide a solid footing.

It also pushes us back to fundamentals: design for disassembly, design for repair. If a mounting system can be easily unbolted and the material recovered at end-of-life, that closes the loop and mitigates long-term scarcity. It’s a principle that feels obvious in theory but is often sacrificed for installation speed.

The Human Factor in the Field

Finally, all this tech and these components end up in the hands of installers. The best fastener in the world is useless if it’s over-torqued, under-torqued, or installed on a compromised surface. The skill gap in the trades is a tangible risk. We implemented a toolbox certification program on our sites, where crews had to demonstrate proper use of torque wrenches and understanding of load distribution. The resistance was initial—it was seen as slowing things down. But the data showed a dramatic drop in post-installation tension checks failing.

This is the gritty reality of building a durable green tech ecosystem. It’s not just about R&D labs; it’s about training, manuals that field crews actually read, and creating a culture where the quality of the bolt job is as respected as the efficiency of the inverter. The future isn’t just manufactured; it’s constructed, one connection at a time.

So, is the footing solid? It’s getting there, but only if we pay as much attention to the nuts and bolts—literally and figuratively—as we do to the headline-grabbing breakthroughs. The transition’s resilience will be determined not by its most advanced component, but by its weakest physical link. That’s where the real work is.